THE HISTORY OF THE POLISH INVOLVEMENT IN ARTS

They can be found in our homes, sometimes in cabinets or cardboard boxes. Sometimes we have them in our home studios on the easel or on the workbench. Paint tubes: the ones we just opened, the ones that are almost empty, and the ones we rarely use even though we really liked the colour. Some paints have historical names like Burnt Sienna Earth or Prussian Blue. Some have paint-stained caps that are now hard to close. There are paintbrushes in various sizes: the ones we got so used to that we don’t want to throw them away even though they are completely worn and almost useless; the ones we like the most, and the ones we almost never use. Additionally, there are varnishes with peeling and stained labels, bits of charcoal, Gesso primer. Empty canvases look at us inquiringly, waiting to be used. We can never remember the first paints we were given, but we always remember the first tube we bought. It’s hard to say how many hours we spent on drawing or painting alone to the sounds or music or in the silence of our thoughts. The space of the studio doesn’t matter, what matters is that we have one in the first place. Sometimes we take our “creative freedom” for granted, like something obvious and treat it like the things we love unconditionally. But there is nothing obvious in the story we want to tell you.

1894

France, 1894. The Lumiere brothers invent the cinematograph. Claude Monet is finishing up his “Rouen Cathedral” series of paintings, on which he started two years before and which would become a true icon of western art. It was an artistic paradigm composed of 48 paintings, all with the same theme. It was an artistic venture, which involved considerable internal misunderstandings with the artist and which is now one of the symbols of the birth of contemporary painting. For the first time in the history of art, a painting story is interrupted. Looking at it with contemporary eyes, we could easily compare the “Rouen Cathedral” to Andy Warhol’s “Marylin Monroe”! The amount of work put into it by the artist was tremendous. Monet wrote the following in a letter to his friend, Clemenceau: “The canvases could have taken fifty, a hundred, a thousand, or a lifetime of minutes […] My stay here continues: this does not mean that I am close to completing my cathedrals. The more I see, the harder I find it to demonstrate what I feel and I keep saying to myself that the ones who claim to have finished a canvas are horribly arrogant. […] I am forcing myself to work and am making no progress, I am stumbling in the dark and accomplishing very little, but I still feel exhausted.”

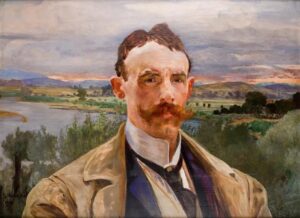

In the late 19th century modernism was making strides and knocking on the doors of European history and culture. In Poland, the “cursed painter” Władysław Podkowiński paints the “Frenzy of Exultations” and displays it in Warsaw. It creates a major social scandal but is still able to attract 12 thousand people in the first month of the exhibit alone. Podkowiński is shocked by the scandal and cuts up the canvas with his knife in an attempt to destroy it; he will die of madness and tuberculosis just a year later at the young age of 29. That same year Malczewski paints “Melancholy”. Four years later, the phrase“Young Poland” was conceived. In the dynamic and artistic Kraków there is a young and promising artist named Józef Karmański. He graduated from the Matejko Academy of Fine Arts in the years 1884–1886. He also graduated in chemistry. He painted mainly landscapes, and mastered all known painting techniques, often combining them. After studying in Munich and Paris, he returned to his homeland in 1894 and opened Poland’s first artistic paint factory under the name of Józef Karmański in Dębniki (Kraków). At the time there were very few industrial manufacturers of paint for artists in the world.

There was a small production trade in The Hague, Netherlands, operating under the Royal Academy of Art. In 1870, artist William Roelofs relocated the small plant away from the academic community and shared the formulas with his son Albert, who would succeed his father and establish “Old Holland” in Scheveningen in 1905. Talens & Co, a second Dutch company, would take its first steps in 1899 when banker Marten Talens launched production. It initially focused on office and stationery supplies.

In France in 1720, artist Chardin asked Paris-based pigment supplier Alexander Lefranc, giving him own formulas, to prepare ready-to-use paints. Lefranc launched production in the back of his art store in Paris. In 1853, Lefranc was the first company to put paint inside a sealed tube. In 1867, another talented chemist, Joseph Bourgeois Aine, opened a colour lacquer store and laboratory in Paris, which became a major competition. The two companies would merge in 1966 and become Lefranc & Bourgeois. A small workshop was also opened in Paris by pigment vendor Gustave Sennelier in 1887 under the name of Maison de Sennelier. His passion for pigments led to the development of a broad spectrum of colours, especially pigments contained in sticks which are known today as pastels.

England had the George Rowney Company, which has been making art paints since 1793. It was started by two pharmacist brothers, Richard and Thomas Rowney. They had success as manufacturers of wig dyes and perfumes but needed to reinvent themselves when the King of England, George IV, threw his wig on the ground and made it fall out of favour throughout the country. Their successor, George Rowney, was the first to put paints in lead tubes instead of in jars or brittle glass. Additionally, London had Winsor & Newton, which was established in 1832 out of the cooperation between an artist (Henry Newton) and a chemist (William Winsor) . They took the first steps in manufacturing watercolours in a way that was innovative at the time.

England had the George Rowney Company, which has been making art paints since 1793. It was started by two pharmacist brothers, Richard and Thomas Rowney. They had success as manufacturers of wig dyes and perfumes but needed to reinvent themselves when the King of England, George IV, threw his wig on the ground and made it fall out of favour throughout the country. Their successor, George Rowney, was the first to put paints in lead tubes instead of in jars or brittle glass. Additionally, London had Winsor & Newton, which was established in 1832 out of the cooperation between an artist (Henry Newton) and a chemist (William Winsor) . They took the first steps in manufacturing watercolours in a way that was innovative at the time.

In Prussia, the centre of art paint production was Dusseldorf. The oldest company in Germany is “Lukas”. This brand was established in 1862 by Dr Franz Schoenfeld, whose father owned the oldest art store in Germany, located by the entrance of the Dusseldorf Academy. The company was named after Saint Luke (Luca), the patron saint of artists. In 1881, a rival art paint factory appeared in Dusseldorf when Jozef Horadam and Hermann Schmincke (former associates of Schoenfeld) launched production according to the formulas of Italian academic painter Cesare Mussini. In the recently unified Kingdom of Italy, the cradle of art, there were no art paint manufacturers whatsoever. The first art paint production in the beautiful country would not come to pass until the early 20th century.

In 1894, Alexander III Romanov was the last Russian emperor to die of natural causes. “Khon” opened in Saint Petersburg in 1853 and made a reputation for itself with a distinct offering of art paints. The manufacture would get captured in the angry winds of history and bolshevism.

The industrial era started in the 19th century in Europe and painters can no longer afford to keep young apprentices making their paints by hand in the studios. A new social group also emerged: artists. The 19th century also gave birth to contemporary chemistry with laboratory-made pigments and dyes, as well as pigments obtained from metals such as lead, cadmium, and cobalt. These were favoured by impressionists as well as expressionists. Could Vincent Van Gogh have painted the “Wheatfield with Crows” without his new cadmium yellow pigments?

POLAND

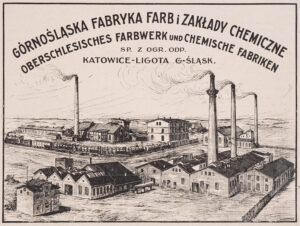

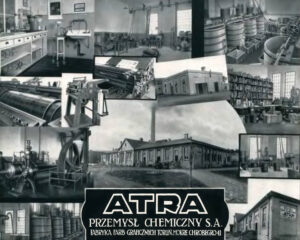

But let’s get back to Poland. The Karmański factory kept growing until the death of founder Józef Karmański in 1904. The beautiful portrait of painter Józef Karmański painted by Jacek Malczewski is now exhibited at Kraków’s Pinakoteka Gallery and considered a national art treasure. In 1904, “Karmański & Co” became “Gabryel Górski & Co” and relocated from Dębniki to Zwierzyniec. Its paints were held in high regard both in Poland and abroad. The art paints made in Poland were also distributed in Vienna, Budapest, Prague, Sofia, Munich, Venice, and Milan. In Poland, the factory made oil paints, pastels, watercolours, inks, pencils, canvases, carpentry for artists, and numerous other accessories. In general, the art paint production industry in Poland grew so much in the 1920s and 1930s that oil paints and watercolours would also be manufactured by its historical rival in Warsaw: Leszczyński. Additionally, there was a small stationery ink factory in Poznań operating under the name of Orion. When it comes to printing ink, the leader of the era was Atra in Toruń, while Zachem was the undisputed king of pigments. In the early 20th century the Polish textile industry was very advanced and had a great impact on further chemical and associated dyes industries development. This was a time when tailoring and textiles had new materials and new colours to work with. Fashion was on the rise.

In 1918-19 Karmański was acquired by industrialist Marian Chyzewski, the successful owner of Iskra chemicals. The merger of Iskra and Karmański produced the third biggest and most prestigious factory in Kraków at Lubelska Street. In the Second Polish Republic, “Iskra and Karmański” employed over 300 people and had numerous manufacturing departments, the leader being product packaging. Just before World War II, there was a small oil paint trade in Warsaw, which was operating at the Academy of Fine Arts under the management of Professor Antony Buczek. The country was thriving and growing and the sector of arts was no exception.

In 1918-19 Karmański was acquired by industrialist Marian Chyzewski, the successful owner of Iskra chemicals. The merger of Iskra and Karmański produced the third biggest and most prestigious factory in Kraków at Lubelska Street. In the Second Polish Republic, “Iskra and Karmański” employed over 300 people and had numerous manufacturing departments, the leader being product packaging. Just before World War II, there was a small oil paint trade in Warsaw, which was operating at the Academy of Fine Arts under the management of Professor Antony Buczek. The country was thriving and growing and the sector of arts was no exception.

The outbreak of war shattered everything. The building at Lubelska Street was still standing as the Red Army arrived in Kraków, but all its surviving directors who did not flee abroad were arrested as enemies of the people. The communist party had no plans to manufacture art paints in the new Republic of Poland. Art could not be free in the socialist realism era. A supply agreement was established with the Dutch Talens & Zoon to cut off the wings of all potential attempts to rejuvenate the historical Polish Iskra and Karmański. After the war, Talens would hold a monopoly (guaranteed by the Communist Party) in scope of the broad presence of art supplies in Poland. The exception was the small and underdeveloped oil paint production line of Astra in Przemyśl. This company was making mostly school supplies for children. We would have to wait until the 1990s to see some rival brands fill the shelves of ZPAP stores in Poland.

POST-SOLIDARITY YEARS

After the opening of the borders, in 1995, Apa Poland was recruited to distribute the products of a renowned Italian art brand – Ferrario of Bologna, the small trade established in 1919 by Professor Carlo Ferrario. Like Józef Karmański before him, he was both a chemist and painter. In addition to distributing the Italian supplies, Apa realized that a country as big as Poland needed a domestic manufacturer. History confirms that Polish artists deserved their own domestic brand. In 1998, Apa Poland launched a small and simple production of mediums, varnish, primer, turpentine, flaxseed oil, and a few paints. Starting industrial manufacturing from scratch was no easy task, but – as fortune would have it – APA Poland was able to establish cooperation with one of the oldest Italian art brands, DiVolo, which had been making paints in Florence since 1913. By the 1990s, DiVolo had been owned by the Amorosi family – which took over production in the 1950s. Chemistry professor Luca Amorosi was running the production with his brother Andrea. The respected Amorosi brothers dreamt of continuing to manufacture art paint in Poland! The Renesans brand was launched in the early months of the 21st century and the machinery in Kobylnica (Poznań) produced the first oil paint tubes bearing the Lion of Saint Mark logo, which were completely made in Poland.

Poland had an abundance of numerous materials. It was among the European leaders in manufacture of titanium, flaxseed oil, zinc. Back then it also had balsamic turpentine and pure pigments. That’s where everything started. The name Renesans was chosen for numerous reasons. In the 1990s, Poland was rising from its ashes after many years of struggle and war. Renesans means renaissance, rejuvenation, and a fresh start. This is what everyone in Poland wanted. We also felt that we had a tremendous debt of gratitude towards the Italian market and Ferrario, but mostly towards DiVolo. Italy was the cradle of the Renaissance and we wanted the name to express our gratitude. The Renaissance era was a brilliant and creative time. Its symbols include the winged lion. This symbol represents not only freedom, but also of strength and security. When it came to chemistry, we could always count on the tremendous practical experience of chemist Professor Luca Amorosi. During the first 5 years of production, this collaboration was a key factor. Eventually, we would need to go forward on our own.

Apa Poland and the Renesans brand are 100% Polish. We were able to establish a company, which – much like Iskra and Karmański over 100 years ago – exports quality products abroad. From 2014, Renesans has been present at the International Fair in Frankfurt – the biggest fair for art supply manufacturers in the world. Renesans has become the point of reference for numerous Polish artists and painters. We never stopped in our efforts to grow and tackle major challenges, but Renesans would have never succeeded without the help of Polish artists. It was these artists who made us grow and let us make mistakes and correct them. Poland is a wonderful nation. In the heart of Warsaw, there is a sign saying “All of Poland is building its capital”. These words apply to Renesans as well. “All artists, companies, and individuals who were and still are associated with us built and continue to build Renesans”. The Polish Renesans brand is made up of quality handmade and industrially manufactured art paints and supplies. The factory in Kobylnica currently makes 3 types of oil paint, 8 types of acrylic paint, 3 types of watercolours, temperas, gouaches, several types of inks, varnishes, media, solvents, graphic designing products, gilding and conservation products, hobby supplies, painting supports, and various accessories.

Poland really did experience a renaissance. Artists are always willing to face the future with curiosity, courage, and tradition. This is what the winged Renaissance lion – a part of the common history of all of Europe – stands for.

Artists, we thank you!